Life Back Outside the Comfort Bubble

Cancer Sucks

Yesterday I saw a woman wearing a “Cancer Sucks” shirt at lunch. Not noteworthy in and of itself even in a country where English is mostly a second language. The fact that the lettering was 4 inch high and reminded me of the Van Halen tour shirt I purchased in 1991 that my wife won’t allow me to wear (as if it still fit me) because it had the initials of the album in 4 inch letters on the back. I thought of those I’ve lost to cancer and those I’m losing to the disease and went on about my day.

This morning the locked screen on my phone showed notifications that I lost one of those friends. Ginger wants me to stop cussing. The first time I typed this I used a colorful metaphor and my computer promptly restarted the webpage so this time I’ll edit myself.

Full Unlawful Carnal Knowledge Cancer—in four inch letters.

Not a good way to start any day. With heavy heart I walked downstairs to begin my normal daily routine of coffee, bible, and German lessons. It did not go the way it normally does, go figure.

In Afghanistan, almost every day started with a cup of coffee (and my bible reading) that came from my Battle Buddy, Pamela Kelly-Farley. She was Program Manager for the same half of Afgahanistan that I was Resident Engineer over. Together we solved as many of the problems of our mission that were humanly possible. Plus a few. Our nicknames were Thunder and Lightning. Everyone saw the bottle-blonde with big boobs, Lightning, and everyone heard the loudmouth SOB who has been told he needs to talk less since first grade, Thunder, Me.

Once I returned to the “welfare check” life of non-deployment Corps work we lost touch a bit. Then in Sep of 2016, two years after I left, she called. We talked a few times on messenger. Then in January her husband THE Chris Farley (OK, he’s A, but still), messaged me to tell me she had been diagnosed with pancreatic cancer. The FU of cancers. I knew what that meant. I’ve lost friends to that one before. Alex Trebek may be beating it but probably only because he makes his doctors talk in the form of a question.

We tried twice to catch up since then but the most we had was one brief 45 second chat in May. She was having her hair done. I know that made Shameless feel better and I could see her wearing a 3 carat ring in sweat pants while she did it. She had been in hospice care and I know doing something for her was what she needed but God do I ever wish I had selfishly made her stop and talk to me.

Back to this morning, I made my coffee in a cup that was the same size and make of the cup we drank from there. No surprise, I had this cup in Afghanistan but it was not the same one I drank from each morning. My cup says “Happiness is Camp Stone Afghanistan. . . in my rearview mirror.” The one I drank from was a Bagram Airfield cup. Taking a breath I opened Facebook.

The very first post I saw was an ultrasound. Of another friend from KAF. Death. Life. Double-whammy. Life is good, cancer still sucks.

After reading a few posts, and posting a few condolences I started my German lesson. The very first phrase to translate was the one on the right. I snapped a screen shot before verifying it was correct, but it was. Sie ist nicht zu ersetzen. She cannot be replaced.

I have to admit, it’s been a rough day. I can always think of something to say. Once I even talked and dozed off at the same time without missing so much as a prepositional phrase. Until today.

At least until now. Perhaps I’m trying to make myself get over it. Maybe I hope her family and our friends will read this and it helps them come to grip with our loss. Or maybe I just really am a loudmouth SOB screaming into the aether that is cyberspace. There is no Thunder without Lightning, but it does still echo.

On the way home I got caught in a sudden, intense rainstorm. After learning that the speed with which the convertible top goes up is inversely proportional to the intensity of the rain coming down (I call it Waiting for Peugeot, but it means I got soaked) I thought about Pam and my thought was that now she could be with me and I don’t even know. There is a level of mysticism and other-worldliness that I’m not trying to go into here, but I thought it. Then of course thought it would be easier if the top were down again. Not the point though.

I turned and followed a detour, then once i returned to what is my normal route home I saw a rainbow. The end of which was located in roughly the exact location of the intersection in which I had my thought. As I rounded the corner I could see the entire rainbow. From horizon to horizon. Don’t get mad I didn’t take a picture of that, I may or may not have been moving when I took the first picture.

When I first thought about what to say in this post I thought sure I’d end on the ultrasound picture. But God had a better plan. A better ending. And nothing is better than a rainbow. A promise from God.

Serendipity takes me everywhere. She always has and probably always will. And yes, quite often She looks like (and is) Ginger. Serendipity oversaw my entire day. And to me Serendipity, Coincidence, Karma, and Luck are all synonyms for Providence. Providence has always steered me. It steered me to Afghanistan and to breeze into Lightning’s life.

And until we meet again, the question remains: Cocktail or Pool? No fair rubbing it in that you have both, Pam. It only counts when we enjoy them together.

The First that made the Worst

Discussions of Hitler occasionally mention that at least the trains ran on time, without any consideration of where these mythically prompt trains were running to. Last weekend I went to one of those places. Though the trains didn’t always run there, eventually they did to the detriment of all who rode.

Last weekend I completed the trifecta I never imagined completing. I went to my third former concentration camp, Dachau. The mother of them all. The first camp whose deputy went on to create the worst camp. It was, like the others, a sobering and surreal experience. No trip to a concentration camp is without moments of incredulous shock at the atrocities that were done, but despite being prepared to have that experience, Dachau still found ways to shock.

If you read either of my earlier posts on Auschwitz or Flössenburg I mentioned that on the way to see the first camp Lizi and I discussed visiting more than one to see if the treatment of the camps were the same in Germany as they were treated in occupied Germany. Once again, our theory was confirmed. They are different.

Dachau was created specifically to be a prison for enemies of the state but even though all were prisoners, there was a dedicated prison cell building, The Bunker, behind the massive main building. Where Aushwitz was more preserved (almost no former barracks were removed) Dacahau, like Flössenburg, has had almost all of the barracks removed. Two actual barracks remain and 32 footprints are clearly defined stretching out towards the crematorium. What we think of as the camp itself was only a small portion of the overall installation though.

In addition to the prison camp there were SS Officer quarters, training facilities, farms, and a whole slew of buildings which are not part of the memorial site. Distrubingly, the location was used as an American installation after liberation. The US Army even put prisoners in The Bunker, though they did remove the standing cells which were particularly cruel and inhumane. Then in the late 60s and early 70s as the memorial was being set up the majority of the installation was turned over to the Polizei. It is still being used albeit in a manner that precludes the public from ever seeing it.

The far back corner of the memorial, which would have been inside the heart of the overall installation, was the crematorium area. The first crematorium still stands but when it could not keep up the pace a newer one was built nearby. The newer facility also included a gassing facility disguised as a shower room very much like Auschwitz has, the only difference being that the Dachau facilities were never used. No one understands why which I find interesting in and of itself. Was no one who had run the place asked? Are they sure the rooms were never used? It is a very elaborate system to construct so simply having a go-by example makes little sense yet that’s the best guess we can form now.

It is still a haunting statement so I’ll say it again. The first crematorium was too under sized. It could not keep up. It did not have sufficient capacity. And this was a labor camp, not a death camp.

The atrocities committed here were no less severe than the atrocities committed in other camps, especially to those on which they were done. To say there were perhaps fewer atrocities committed here lessens the fact that none were excusable, allowable, or forgivable. That is not what makes the treatment different in this case.

The memorial at Auschwitz was all about the victims and survivors. Not only were the camps run by Germans, the citizens of the town were removed and taken elsewhere. The city was repopulated by Germans deliberately so that none of the surrounding residents would know what was behind the wall much less what went on there. On the grounds, there were former barracks dedicated to each race, nationality, and religion that had been imprisoned, tortured, brutalized, and attempted to be exterminated. The only real discussion about the captors was one on Rudolf Höss. After touring nearly all of the facility the last two things to see are the crematorium and the gallows on which Höss was hung. At that point it is a feel good story to see that he was hung right next to the crematorium and within sight of where he and his family had lived. Where after the end of a long day of terrorizing, dehumidifying, and desecrating everything good about living this demon went to spend time with his wife and children. He was hung within sight of where he had enjoyed life and family. And fuck him for making us feel good about him being hung, too.

My visit to Auschwitz was so powerful I still feel the need to discuss it in detail when the point of my post is a different camp. It is that emotionally strong.

The memorial at Flössenburg had a great deal about the captors. Here the captors were not just Germans, they were fellow Germans. This was where they were from. Where they had lived and played and grew up. At the end of the war this area was still German. There was a lot about the victims and survivors here, but they shared the stage. While most of the buildings here were torn down, even the footprint of the camp was removed. Today there are houses that were built upon the location of some former barracks of the camp. There is no barrier between the town and the memorial. It is open, wide open to the city that remains.The Mound of Ashes and crematorium are hidden from view of the town, but that was where they were originally built—out of sight.

The memorial at Dachau has memorials to the victims and survivors. I was there three weeks after their liberation anniversary. There were several 90+ year old survivors that had been in attendance for the ceremony. There was information about what happened, the history, the coverup, and how the process spread. It was regularly “cleaned up” for propaganda visits, at least early on. It did serve as a model for other camps. At one spot there was a board showing the “career arc” of the leadership of Dachau. It showed where the important members of the leadership went on to serve, set up, or be a part of the overall labor and death camp systems.

Living in Germany, not just visiting it, has given me a unique opportunity to get to know Germany and its people. I have friends, close friends who are German and I can talk with them and pick their brains on life and living here. When you first come here they tell you that most Germans do not want to talk about the 12 year period that includes that dark time. There are 2000 other years of German history to discuss. But I’ve been here long enough now that they’ll talk to me about that part too. It isn’t that I dwell on it, it’s just that it is that 12 year period that has allowed me to come do what I do here. And the question that we all want to know is how can these people, who are so kind and helpful today, have been led down that path.

Looking back 2000 years into German history explains the reason they are the way they are. It explains why they could be led down the path they were led. But looking back over the last 75 years explains where they are today. They have taken such a shift that all life is sacred to them now. I had a massive hornet nest in my shed. Not bees, not wasps, hornets. Ugly, nasty, loud, big stingers that stay on the insect not in your arm, huge hornets. Not only is there no hornet spray in this country, you can get fined up to 50,000 Euros for willfully damaging or killing them. One of my projects at work is to replace guy wires on an antenna that is in danger of falling down. If it falls it has the potential to land on other buildings and possibly even kill humans if they’re unlucky and happen to be where it goes down. The whole project, to save a structure and make it safe for people, was threatened because of an ant hill at one anchor point. If the ants had not decided on their own to move the project would have been canceled. Why mention that here? Because of the life I found in the camp. Ant hills and wasps. I don’t think the ants show up, but the wasp does. Life moves on, and a respect for life is now evident. Not just in the memorial site but throughout the country.

Life rules. Life is good. And that is what memorials like this hope to convey to their visitors.

But When I was 8

A few days ago a random picture of the Parliament Building in Budapest appeared on the TV. Googlecast was playing a slide show, it wasn’t one of mine. Faith, my 8 year old said, “Daddy, that’s in Budapest!” Because we had seen the building, a beautiful building, when we toured back in November. This (like so many other things) got me thinking.

By the time I was 8 I had gone to Jackson, 3 hours away. I had been to New Orleans, and the panhandle of Florida. Went into the Holiday Inn where they filmed the opening scene of Jaws 2, it was exciting. My furthest trip was to Aunt Nancy and Uncle Junior’s. We’d gone their plenty, about 5 hours away in the heart of LA. The original LA, Lower Alabama. I had not even made it to Georgia yet, that wouldn’t be until 10 when I went with Uncle Junior to fish in Georgia, and it wasn’t until 13 I made it to the big city of Atlanta.

When I was growing up the menu at McDonald’s overwhelmed me with options, whatever will I get? I remember standing in a Taco Bell on the beach (near the Beer Barn) and thinking what’s a belgrande because I had no clue. I didn’t get to eat fast food.

Faith is a different issue. She asks for ‘her usual’ when we go to McDonald’s, or Popeye’s, or several other places. She asks, “Remember when we were in Paris?” and identifies places and things that I’m more drop-jawed and google-eyed for seeing than her because I’ve heard of these things my whole life and never really knew I could get to see them. I’ve seen things built by the Romans and what did the Romans ever do for us?

So what’s my point? I don’t know, I love that I’ve given my daughters a chance to see things halfway around the world. I love that her world includes parts outside the sweet, heavenly comfort of the Deep South. But where does it go from here?

Byrd's Sawmill

Recently I cracked open an aging can of gold that I have very carefully kept with me through every move. From the first house on Benachi, to the second, to On the Green, South Alabama and back twice, to Washington State twice, Louisiana once, Hueytown, Cropwell, and Fairhope I have hand carried this once growing container full of stuff. The only time I didn’t bring it with me personally was the move to Germany and don’t tell Ginger I was nervous about it the whole time until our household goods arrived.

Amongst the treasures I found was a gem of an article written by Mr. Dale Greenwell on The Byrd Sawmill. There are lots of articles by Mr. Greenwell, Edmond Boudreaux, and Walter F. Fountain in this case. Everything except for the first article by Mr. Fountain that got me started saving this stuff to begin with but that’s a different story (literally and figuratively). So I re-typed the article here to share. It was printed in the Biloxi-D’Iberville Press (the name may have changed by then but I only have the article not the whole paper) in Nov 2005, so most of my family was a little preoccupied with other things then catching up on history. Namely they were busy throwing out water-damaged and moldy history. It is not my work and I do not have any permission from anyone to re-print it but as my purpose here is to document and provide it for other relatives of the man I never heard call Charles, only rarely Everett, but mostly Bossy, I hope I can be forgiven. Uncle Cleo and Granny get mentioned as well as a photograph of a few other closer relatives

There was one word error I left and one missing punctuation mark I added. I also didn’t capitalize french because I stopped capitalizing france and french in 2004. My trips to france made me happy to have done so. Other than that it is re-typed verbatim, unless my fingers slipped. I hope my family enjoys it as much as I did reading it, and yes, there’s a strong possibility that it’s going to appear in my oldest work in progress as I continue to wallow in early 20th Century Biloxi.

The Byrd Sawmill

By Dale Greenwell

Biloxi-D'Iberville Press

Nov 18 & 25, 2005

Over the weekend I had the opportunity to take a ride with Webster Lee through the wasteland of what used to be D’Iberville, then I visited with Andy Balius, who now owns part of what once was the first industry on the north shore—the “old brick yard.” It was a trip down memory lane, a nostalgic but painful trip.

Remembering what once was. Remembering where my folks and your folks once worked, played, lived and, well…Andy and I walked along the waterfront, aware of the brick fragments that marked the site of the Biloxi brick factory, and before that the french colonial brick yard. The 1723 storm had put it out of business, but it was reopened after the Civil War (The War of Northern Aggression). It was the source of bricks for many of New Orleans’ buildings, and more than a few of our own.

By the time the factory had reopened, the Coast had moved from schooners, as the principal source for moving materials between cities, to railroads and steam-driven boats and barges. And with the railroads and steam engines came the first major industry to the Coast and the South: Timber.

Until then, as I’ve reported more than once, charcoal, turpentine and bricks were the industries, albeit nothing major. Then the rails made seafood king on the south side and timber king on the north side. These industries created booms that encouraged thousands to emigrate here.

In the last years of the 19th century and the early years of the 20th, the brick yard immediately west of 7th Avenue, and the Dantzler Mill at Vennie (Cedar Lake) were the major industries on the north side. By 1926 both were closed. Brick factories had sprung up throughout Mississippi with ready access to rails, and the huge yellow pine forests had been reduced to stumpage. Of course, this played havoc with the turpentine industry.

Yet, some men found scattered strands of timber that had escaped the large corporations’ axes and saws. These men had grown up cutting trees and couldn’t get it out of their blood. One of those me in the subject of this story: Charles Everett Byrd.

Born in the Ft. Bayou settlement in 1893, he married a girl from there, Agnes Garlott. Before WWI, he was cutting timber, whenever he could find it, in the Jackson County outback. At the time, logs had to be floated down stream or drug by oxen through woodlands and swamps to mills, like his, that changed locations regularly.

While Dantzler was in operation, Charles, like other independents, hauled his lumber to Dantzler’s where it became lost in the millions of board feet shipped annually to Europe via Gulfport and Ship Island on four-and five-masted or steam-driven ships.

As forests diminished, Charles moved westward, toting his little mill with him. The family built a home and lumber supply business at the intersection of Strawberry Lane and Caillavet Street in Biloxi. His logging camp and mill were now at Palmer Creek, near the camp around. Chryle (Shrill) Warden joined Charles in the founding days and remained with him to the end.

The business had a truck, but four oxen and two large white mules did the hauling through the rough of the Mississippi woods. After the timber was milled it was hauled by truck to Biloxi, to be sold in the Byrd’s Lumber Yard—until the bottom fell out of the market.

The depression following the crash of 1929 destroyed the real estate and building boom throughout the world. The family lumber yard and home did not escape the wrath. After losing all but pieces of mill equipment, the oxen and the mules, Charles started over, including a deal with Dantzler for several pieces of mill equipment left in the large, vacant building on Cedar Lake Island, where trains once unloaded logs from the forest and loaded barges with lumber bound for Europe.

By skiff and truck, Charles gathered his assets and moved them to a spot at Holland Grantham’s dairy, just west of what is now Central Avenue. The mules and oxen were with him. After all, without them there could be no timber. The were the skitters and tractors of the timber men in those days.

On July 1, 1932, in the midst of the Great Depression, Charles purchased several acres of land between School House Road and Tiger Branch (today, the northwest corner of Quave and Gorenflo Roads), where he set up operations. Before long, cabins, an office and a home were constructed.

Well, I’ve run out of space. If you don’t mind returning next week, we’ll finish the story of Byrd’s Saw Mill. So, until then, keep your lamp in the window.

Dawn is an hour away when the match is tossed into the oil splashed slabs of pine scraps inside the boiler. And before the shades of gray lighten in the eastern sky, a bit of steam generated in the flier is released through the whistle. Lamps appear in windows, and before long men are on their way to the mill.

That was the beginning of a hard day’s work, if you worked at Byrd’s Sawmill and Lumber Yard, in D’Iberville, before and during WWII.

If you perused through last week’s article, part 1, than you know where we are. The mill, after being dragged through Jackson and Harrison Counties from pre-WWI to the early depression years, finally settled in D’Iberville, between shell-paved School House Road and Tiger Creek, what is today the northwest corner of Quave and Gorenflo Roads.

In 1932, the first part of the property was purchased with hard earned money (in the depression, all money was hard earned) by Charles’ son Cleo. From then until 1937, the family purchased adjoining parcels from company profits, eventually realizing six acres.

By WWII, the property was fully developed. A new home for the Byrd family, an office, a small house and four cabins, a community wash-shed, water well with pump, saw horse with a steam engine with fresh water ponds, lumber drying racks, materials shed, and outdoor privies. Two of the basins (“camp cars”) were two small rooms built on skids, to allow transfer. Two were shotgun three-roomed houses with front porches.

Let me back up a moment. In the beginning at this location, water for the steam engine was hauled from the artesian well at D’Iberville School, a block south. A wood-burning stove and lamps served theme. Eventually, an electric line serving Grantham’s dairy was extended through the woods to the Byrd home. The nearest store was at Five Point, three blocks south. The nearest neighbors were the families of Jake Quave to the east and Columbus Parker to the south.

“Monkey” Shoemaker, Chryle (pronounced Shrill) Warden and “Smitty” Smith were Charles’ principal employees, until Charles passed away on No 12, two months after the “47 Hurricane.” The mill never reopened. Until then, Smitty and Rosie were the only blacks residing on the property. She worked in the Byrd home.

The Wardens lived across Tiger Branch; other employees lived on the premises.

Byrd’s crew cleared land on what is now Keesler AFB. His oxen, which were more like pets, were turned loose after work to graze in the area, then were hitched again to a 10-wheel wagon the next morning to drag logs out of the bogs and woods to the log truck. At that time, logs came from virgin pines, which were usually from trees more than 100 feet tall with girths of 15 feet plus.

The “Yard” handled a large variety of building materials, including sheetrock, windows, doors and hardware. People came from as far away as Hattiesburg to buy from Byrd. After Charles’ death, everything was sold. The Page family bought the storage building and moved it to their lumber yard in Ocean Springs.

Oh, I forgot to tell you about the oxen, Bess and Blue, going astray and dining on sour mash from the Garlot whiskey still near Ft. Bayou. WEhn they sobered they completed the journey to D’Iberville.

Monkey sleep with these oxen when the mill was at Grantham’s He cooked outside and is remembered for his skillet break. When he passed away, his corpse was placed in a pine coffin made at the mill yard.

During the early 20th century, when infectious diseases were playing havoc with southern cattle, the vat on Byrd’s property was used by local to dip sheep and cows.

Agnes passed away at age 92 in the 70s. Last spring I visited the Byrd property. Only the home, office and vat remained. Of particular interest was the unique variety of planking in the old house. The office had become a storage shed. The family has expressed an interest in preserving the vat (also uniquely constructed) for posterity.

Charles’ grandson, Scott Byrd, now owns the property.

In its working days, this small industry in the heart of D’Iberville, like the few seafood factories, signaled its employees (and the community) that it was time to go to work. But Byrd’s whistle also marked the end of the day with a few toots.

I wager there will one day be an historic marker at the site. Let’s hope so. Until then, keep your lamp in the window.

Aunt Maggie, Uncle Curt, and Uncle Pat at the sawmill in 46, Dad must have been in the house somewhere.

Thanks

Most people know that someone who speaks two languages is a bilingual person. Speaking three languages means you’re trilingual. But speaking one language mean you are American.

It has now been over three years since the Next Great Byrd Adventure began. It has brought a lot of changes to my family and my outlook on life, the world, and even my view of the United States. I remain a proudly arrogant American by birth and Southern by the Grace of God, but I see my country better and different from having been outside it and experiencing life in other places. One thing that cannot change is that Southern heritage. Growing up in the South means you learn sir and ma’am as well as please and thank you and it’s that last one I want to talk about most.

Within a month of moving to Germany I already felt bad about myself. While I knew practically no German the Germans around me all knew some English. More than enough to be able to communicate. Oddly, I learned that saying “Mein Deutsch ist schlecter den als Englais” poorly simply emphasizes the fact that my German is worse than their English. The reason this makes me feel bad is that I never bothered to learn Spanish. Like most Americans I have wrongly not learned a way to communicate with the influx of Spanish speakers prevalent all over the US. They are to my home what I am to my current home. And why not learn a way to communicate to help them? What does it cost, what does it hurt, and more importantly isn’t it the kind thing to do?

On one of my earliest international trips, I believe I was headed back to Afghanistan at the time, I met a drunk Dutchman. He was a big, heavyset, red-nosed drunkard. As I talked with him he commented, “Everyone learns English, or German, nobody ever learns Dutch.” He went on to board the plane but left me with two thoughts, the first was a memory that I had always wanted to learn Dutch. I knew it was a small country with a small population of native speakers but I found it interesting. But after having me him, I lost my desire. The second thought was that the first foreign language I ever learned was at a church picnic (I believe at Flint Creek). I met a South African who taught me several Dutch phrases. She wrote them down on a paper plate which makes it seem funny to me that the only phrase I remember was Ek is hunger. Who can’t remember a plate that says I’m hungry?

Tying all these seemingly unrelated topics together, the easiest thing to learn in any language is thank you. Gracias, danke, j’an qujeh (I can say it even though I can’t spell it), tashakor, grazie, even merci are all powerful words that even if they don’t open a door are able to make whomever you are dealing with feel appreciated. Nowhere did I find this more apt than when I was in Budapest. Hungarian is a tough language for an English speaker, and moreso than in Germany (which was hard to beat) I found the Hungarians to be excellent multilingual communicators, especially in English. Then, at the end of my interaction with them I said the single word of Hungarian I knew, kurzenam. That one word made every single person I said it to smile and most became exuberantly happy and talkative.

Having been able to experience 18 countries has been nice. Being able to say thank you in 8 languages is rewarding. Neither is the largest of numbers that will win a contest for places been or languages spoken, but it is the greatest of accomplishments. The only thing that can overshadow that accomplishment is to learn to say thank you in language number nine.

Amnesia Lane

Instead of working today I dug out an old briefcase I’ve been carrying around and went through it. This case is one I have physically carried to every house I have ever moved to with the exception of this one. I had to leave it in the household goods for the European move and I was not very comfortable or happy about it.

Over the years I have added to it, but have never gone through it. The last time I added to it has been over a decade. So what might be in this container that is of such importance to me? Clearly something near and dear to my heart, this case contains notes and research for the majority of the stories I am working on. Most have been transferred to digital media by now but not all.

There are several incomplete ideas, a few I’ve tied into other stories. Some I completely forgot about. One story I thought I’d lost forever was a re-imagining of the Fall of the House of Usher written in a literary style complete with notes on the symbolism I included. In a few days I hope to post that just for the heck of it. There also was a little post it note with the date 4 Aug 1922 which plays a huge role in my Prohibition Era story but I had forgotten the date.

Most of the case was newspapers that I had intended to clip articles or pictures from or the articles and pictures I had already clipped. Perusing them I was reliving the days just before Katrina when we didn’t know she was coming and just after when recovery was slowing starting. There were stories from when we still had a World Trade Center twin tower in New York. There was even a picture from before I graduated high school. The oldest articles couldn’t be dated but they were from even earlier. They tell of life in even earlier times, the 40s, the 30s, the 20s, even some earlier times.

My Prohibition Era story is one that is nearer and dearer to my heart than the case. In fact, knowing these notes are in it is the reason why the case is important. While the original article is not there any more, I do have a copy of the article I typed so I wouldn’t lose it. Prior to about a month ago I had not added anything to my Prohibition Era story in a very long time. Probably more than a decade. I’m not sure I had added to it since I stopped using the typewriter and started using the computer. Now I’ve added a few things I never thought I’d add and have run out of steam a little. I thought that going through this pile would reinvigorate me and give me another push.

Well, reinvigorated it is. The tromp down Amnesia Lane was good for the heart, good for the soul, and we’ll see soon if it’s good for the story too.

Wondering Aimlessly

My name is Jonathan and I have a sleep problem. Luckily for me, this morning I did not wake up unable to return to a state of slumber at 0130. Tonight it was an hour earlier.

One of the worst things to do when you wake in the middle of the night and can’t go back to sleep is to pick up an electronic device (the one I’m typing on counts as number four). So after reading a few work emails, liking a quote on Twitter, I opened the real time sucking sink Facebook. Among the first pictures I saw was a random shot in the wide open showing a snow-covered field with a mountain in the background. After stealing the photo from him and putting it in this post I noticed that he’s in an odd named place (Chautauqua Park) that by an incredibly strange coincidence is a name that I am about to use in my current work in progress, not the park mind you, just the name Chautauqua, I stumbled across it two months ago and have been itching to use it.

My time in Germany has softened my desire to correct immensely. Ever so much more than is dampened by Muphry’s Law—anything you write criticizing, editing, or proofreading will contain a fault of its own. Even still, I know that if I had been alive and German in the 30s and 40s I would have been employed as a Grammar Nazi. There are things that grate my nerves still. Such as reading something that could of been corrected easily enough (it’s grating my nerves and I wrote it on purpose). The caption of photo struck that chord in me: “Wondering Aimlessly.”

Yet in this regard he truly nailed the essence of what I do on a regular basis. I Wendy, I Wanda, I wonder. I distract myself in the middle of distracting myself and then marvel at the place I find myself in the end. I wander while wondering and wonder while wandering.

Lewis Carroll once wrote “If you don’t know where you’re going, any road will get you there.” Truer words may never have been spoken. And truer words may never have been wondered.

When to Re-Think

I have a lot of theories. Some of them are well thought out and supported. Some are complete hooey. Some are just observations. Most are a work in progress.

That the true English accent is American and that Evolution and Creationism are not mutually exclusive are some of my best thought out and supported theories. The fact that male engineers require more than 4 years to get a degree (Footnote 1) and that all Equal Employment Officers in the civil service are all black females (Footnote 2) count more as observations than as theories but probably belong in the hooey pile anyway.

One theory I have is that people tend to want to be always right (Footnote 3) especially in religion and politics. This also fits nicely with my theory that people want to be able to label others accurately with one word while recognizing that they cannot be labeled in a similar manner. “Oh, you’re a _____. Well I’m a ___-loving, true to heart ____, who ___ when they ___.” (Footnote 4)

Disraeli said, “A man who is not a Liberal at sixteen has no heart; a man who is not a Conservative at sixty has no head.” (Footnote 5) Now I believe his capitalization refers to the British Political Parties and not just the ideological ideals most commonly associated with liberalism and conservatism. Many of the people who quote, or have been attributed as quoting, this change the ages, sometimes the parties and/or political thoughts. The basic idea is the same though, as we age our political beliefs mature and adjust with us.

Only I think that summary is not accurate. People tend to want to be right and adjust if needed, but when it comes to political beliefs I think it’s more precise to realize that we become more aware of our motives and that we may have been misrepresenting ourselves. It isn’t that we have changed from one side of the aisle to the other but rather that we realize more and more that the side we’re sitting on does not portray us as much as we previously thought. It isn’t that we no longer believe we were right, just that now we have put enough thought into it (or seen enough of the world) that we have a clearer understanding of what is right and good..

Whether this idea is right or not, my question is when does a personal belief become a “re-thought?” If you haven’t previously thought about a particular subject, especially where you might stand on that subject, when you do decide how to stand is it a re-thinking? Is that a change of mind or just a clarification?

Either way, is changing your mind a bad thing, especially in regards to politics? So often here lately we see people being beaten up, losing trust and supporters, or just generally being run out on a rail because of things they said long ago (even if long ago was last month instead of in the 80s). Is what someone said/believed before as important as what they say/believe right now?

Mind you, I’m not saying we should give David Duke a second chance (Footnote 6). I’m just saying it may not be the same position they had previously, it may not match up or even seem to match in any way, but regardless of if someone has changed their mine, their political affiliation, or just come to a better understanding of their own inner workings, if what they are advocating now seems different than what they used to support it’s less what they did and more of what they now do that makes all the difference.

And at the end of the day, Napoleon Bonaparte was right when he said, “In politics, stupidity is not a handicap.” (Footnote 7)

Footnotes:

While writing this I found myself getting distracted and adding parts that didn’t really allow the rest of the piece to flow so I added them as footnotes instead.

1) I’ve met 3 males (excluding service academy graduates) who have gotten an engineering degree in 4 years. To a man they have all taken at least one extra semester (or quarter) to do it. This information may be slightly skewed because of the number of SEC school graduates I know that just wanted to get one more season of free football tickets. Females can easily do it, in fact I do not know very many females who took more than 4 years, one did it in less, and at least two didn’t do it in four also just wanting another season of football tickets.

2) I’ve heard of 2 EEO people who were not black females. One was Hispanic the other was a white person that sued to get the job. The real common thread is gender but I’m sticking to my theory and not revising it just yet.

3) People tending to want to be right can start a lot of arguments. Not because they argue they would rather be wrong though. The knowledge that they are right spurs them to argue with you if your statement contradicts theirs. Also, few things can end an argument quicker than simply saying, “You’re right.” And in this matter I am not simply pulling from my nearly 27 years of marriage though the statement has certainly helped to increase that number of years, too (sidetone this is not to say I just agree with Ginger to end arguments but would it be wrong if I did?). And yes, that’s a tangent in a tangent or a digression in a digression. Layers and layers of onion but at the end of it all it’s still an onion.

4) I recognize this explanation would be better if I filled in the blanks but it can go either way. If I say liberal and use conservative examples people will say, “Aha! So you’re a Republican.” If I say conservative and use liberal examples people will say, “Aha! So you’re a Democrat.” There is someone reading this right now trying to figure out which side of the aisle I am on and I just don’t want it to be that easy to discern—yet. It is very easy to look at where I grew up—inside my Comfort Bubble—and who taught me and put me into a classification bucket. Once a friend on Facebook’s wife did such a thing including literally calling me a white boy. The really funny part was that she said I would jump to conclusions without knowing anything about a subject or bothering to do any research. While she was busy doing what she convicted me of doing I had been busy researching the subject.

5) There are many different attributions and versions of the quote I’m about to use but I’m choosing to quote a quote investigator who quoted Laurence J. Peters quoting Benjamin Disraeli not because I believe it to be the first, or the most accurate, just that I like Peters. Also because that last sentence was fun grammatically to type.

6) Not that he doesn’t deserve a second chance, I hope he has changed his mind but also hope he is also smart enough to not ask to be in charge of anything any more.

7) I gave up before I could find a way to quote Groucho Marx “Politics is the art of looking for trouble, finding it everywhere, diagnosing it incorrectly and applying the wrong remedies.” But good grief he’s accurate.

Gotta Be Me

As normally happens, someone sent me something that made me begin to ponder, ruminate, and of course write another post. And as is also normal, over the course of my writing I digressed returning to the main point several times, often in the same paragraph but even in the same sentence. This is a very unclear way of writing and can make it hard to follow. I know that, yet I continue to do it because that is the way in which I think, I write, and I express myself.

But succinct is better. Clarity is better. Typically it is sagacious to eschew obfuscation happens to be one of my favorite quotes because it so spot on describes what should be done by not doing it. And yet, here I go again.

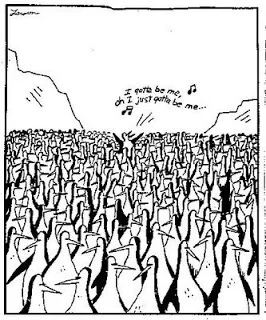

Years ago there was a Far Side comic of a penguin standing in the middle of a field full of penguins singing, “I gotta be me!” Someone turned it into a poster and colored the chest of the singing penguin blue. To some it was the only way it was funny. Gary Larson believed it completely missed the point. It was funny, just not as funny as the original.

When I began this blog my first post said I would be “. . . yelling into the world wide web [to] look at me, read me.” An overwhelmed voice that continues despite the louder sounds of the winds around it. There truly was (is) a point to it though. It was and is that I have to write, even in my non-sagacious way. It may be easier to get more readers by cleaning up and removing my tangential ramblings or frequent circumlocutions, but it wouldn’t be me. As has been the case in all that I have ever done I would rather be me than just get ahead. It isn’t easy and may not ever work. I may fail to gather a platform of folks that enjoy my writing enough to one day become a commercial success as an author allowing me to quit my day job and simply ramble on writing for a living. But I gotta be me.

What you don’t know about my ramblings is that I often wonder about the people who do read my posts. Am I related to all of them? Where do they come from? Where do they go? How do they find me? And will they ever return?

The analytics on my Squarespace page allows me to see what IP and city the folks that click on my blog are from. That makes me wonder about them sometimes (all the time). It doesn’t say who they are, sometimes only saying that main page of the blog without a post that they clicked on. That really makes me wonder about them. Especially who are they? I’m looking at you Clifton, New Jersey; Menlo Park, California; and Boardman, Oregon. Who is out there reading? I would love a comment to let me know what got you here and what do you think. But I don’t expect them. When they arrive they are lagniappe.

However, you can expect another post in a few days from me. A typical post on an atypical topic. Unless and until I figure out what you want it will be more of the same. Though I suspect that even if I do figure that out it won’t change. I gotta be me, and thank you for your support.

Ask Again

Not long after moving to Germany I began to realize two somewhat odd things. First everything you need can be found on the military installations I work on so you never need to go out to find anything. Groceries, libraries, shopping, fast food, entertainment, fuel for your vehicles, it’s all there. Maybe not every brand choice or selection, but you can get it. Second, there are some people who don’t ever go off post.

Not all of the locations in Germany, or even just in Europe, are like where I live. There are more soldiers where I am than any other location, all four of the places I have offices and regularly go have more soldiers than other places (there may be more sailors, Marines, or airmen at other locations but soldiers are concentrated here).

Ever since I realized there are people that don’t want to go out into Germany and explore I started trying to figure out why. I’ve asked myself, and even others, what they think about it and none of us could come up with a reason. Until I was asked one more time.

At a recent meeting at Netzaberg Middle School I found myself walking around the building with a large group of people that included the principal and a lawyer for the engineering firm that designed the school. The lawyer began asking the principal if they taught language to the students. He replied not really. There is a Host Nation Class in which they talk about things German and some Spanish/English classes but that’s really it. She began to talk about how in German schools they teach English from an early age. Nothing new there, I’ve long joked that someone who speaks two languages is bilingual, three languages is trilingual, and one language is American. And there was a touch of superiority in voice as we spoke.

But then she asked why some of the population never went out and saw the community or the country around them. It was asked with a holier than thou superior tone that I could tell she expected no sufficient answer for. The principal began explaining that the post was built so that literally everything needed was available. Sometimes when the soldier deploys the spouse and family are left here and they need the support that is the familiarity and comfort of a miniature slice of the US surrounded by a fence and Bavaria landscape. And then it hit me.

Not all of the people who are stationed here came here by choice like I did. Deep down you can say that they made a choice to join the Army or to accept orders or even just to go where their spouse was sent. There are people who have lived their entire lives in one town and one state. People who haven’t seen the glory and grandeur of the rest of the US. Folks who live where their grandparents lived, went to school where their parents went, hung out with their cousins for best friends, knew everyone in town, and went to the same school system for the full 12 years. I mean fifth generation in one town kind of folks who have never imagined leaving that town, the greatest town ever founded. But when they joined the military they were taken away to somewhere foreign. Maybe it was a different state, but maybe it was a different continent. Not everyone likes to be removed from their comfort zone. Some very much don’t want to leave their bubbles at all. Those are the souls that never leave post, never see the wonders of a Weinachtmarkt, or a thousand year old city or monuments to battles and wars they have never heard of. Those are the people who can take the opportunity of a lifetime and allow it to completely pass them by. These are the residents of the forest that refuse to see the trees.

I have known people as I describe. I have been one of those people. I no longer fault anyone for choosing to avoid the chance to literally see the world. I also no longer wonder why they don’t leave, I get it. It is not just an arrogant American trait as I once believed. Finally, after having been asked one more time, it all came clear.

Personally I have come a long way from the fifth generation Biloxian who was born a half mile from where I lived the first 14 years of my life. My great-grandparents house, two blocks from my grandparents and six miles from my other grandparents. I went to the same school my parents went and had one teacher my Mom had, part of my elementary school was a school my grandfather attended. I knew everyone in town, graduated with people I’d known for 12 years, and hung out with my cousins so much that it sometimes feel I was related to everyone. I never imagined leaving Biloxi but after I did I never imagined moving back. It is still home, it will always be home. It is clear to me both why someone would take the more travelled road and stay in their Comfort Bubble but also and more importantly I understand that taking the road less travelled truly does make all the difference.

Not Going Away Soon

This picture is from inside the infamous Taliban's Last Stand. Those that have been to it know what it is and probably don't want to go back--unless they've been there an uneven number of times. An even number of visits is best because that means you not only landed but also took off from Kandahar Air Field, Kandahar Afghanistan.

As the name implies, this was the last place in Kandahar the Taliban were before being removed. The walls and ceilings have huge chunks of plaster and rock missing from them from the battle that dislodged them. It is impressive and a testament to the construction that the building is still standing at all. This particular picture is over a door to the exterior.

The door itself used to be a bigger, perhaps even a rollup style door and as the mission began the cables and wiring needed for operations in the building were run inside the PVC conduit which was run around the larger door and its mechanisms. Then upgrades were made. The door was removed and reframed for a smaller, person-sized door (actually a double door). When the need for more data lines became obvious they were run close to, but not in the conduit. The first few were more closely following the conduit alignment but then not so much. The attitude of "we'll fix it later but for now" may have been expressed. Then more expansion, more cables, this time just grouped together with zip ties. Again, run near the original conduit as much as possible. Then just run in the vicinity but still zip tied neatly (?) together. Then some lines just run the shortest distance possible, never mind the old conduit and cable runs, but still grouped and zipped. Finally a few lines were run without even mounting and just thrown over the light before just pulled and supported at the corners without even the fixture for intermediate support.

So what does it mean? What started with good intentions, and an attempt to normalize to regular civilized appearances degraded over time while the likelihood of a return to normal operations decreased. A sort of utilitarian approach which, oddly enough is all that is needed, wanted, or can survive in the area. It isn't that Afghanistan is incapable of governing, guarding, or growing on its own. The attitudes of those around it and in it are more concerned with more important things. Like living. And surviving. Less about having a new coat of paint, or faster internet. They do not want to be Americanized or even Westernized. They are happy with the culture they have and have had. The picture doesn’t prove that, but it doesn’t prove anything. It merely shows a glimpse into what started with the best of intentions that over time has degraded to be just what is needed and not much more.

I left Kandahar during a time of drawdown. In one meeting we discussed the particulars of how that drawdown would be. I don’t recall the numbers now, but there was a set number of people that were the maximum that could leave per day. Doing the math it was a physical impossibility for the number of people on KAF to take the regular flights and have the post emptied by the date it was supposed to. Now today, four years later, KAF is still populated, still going strong, and I imagine that this tangle of wires is still there, with perhaps some new additions.

The Good Shit Sticks

Long ago I learned that you can’t make up the really good stuff. Now, I am a writer, and I tell stories. I have learned that there are techniques and things to do to make a bad story good and a good story better, but you can’t make up the really good stuff. For proof I offer my short but true story The Cake Incident. Today there was a mish-mash of events so interrelated it amazed even me. But it started last week.

Last week I was trying to figure out how to use my 109 hours of Use or Lose Leave. As the name implies you either use it or you don’t. What I discovered, honestly by accident, is that no one you talk to takes sympathy on you when you try to describe how hard it is to schedule two and a half weeks off. The most common “help” that I got was “You can donate some of those hours to (fill in name here)” which came from more than one person. I get it, it’s rough to be me. Never forget though that if we could all put our troubles in a big pile with other people we’d happily pick ours back out of the pile instead of theirs. On to today.

Today I had an in-depth conversation about Poland with a coworker. I talked of the beauty of the country, the excellent exchange rate, an incredibly detailed bit about Polish history to include why it has been wiped off the map so many times, even espoused the stark and sterile beauty of the communist architecture that remains in places, and mentioned it is one of my favorite European countries. It is cold, and I don’t want to live there, but it is beautiful. The other individual has a Polish fiancé so perhaps the man-crush conversation was driven by ulterior motives on the other end of the phone. The ability to have such a conversation with someone else is stop in your tracks amazing. I’m not talking about things I’ve read, heard, or seen in movies or on television. Rather places I have seen and been to with my own eyes. I have touched the soil, breathed the air, discussed the history, spoke some of the language all inside this far away place I never dreamed I would be able to see. The grandiose visions of the future I had in high school never included the ability to have experienced such a thing. And high school itself was on the forefront of my mind today as I heard two different songs on two very different radio stations that were both released in 1989. Again, I get it. It’s rough to be me.

At lunch today a German colleague said to me, “In a perfect world. . .” As he continued to talk, I looked around the room and outside the window then interrupted him to say, “Peter, we are in Germany. It IS a perfect world.”

Tonight, Faith asked me what my favorite continent is. I’ve been on three. I’m not bragging, I know people who have been on six and I’ve met people who have been on seven. People who know me know that I am an American by birth, Southern by the Grace of God kind of guy. A dyed in the wool, unapologetic, arrogantly proud Southerner who busts all kinds of stereotypes because I have seen as much as I have of the world. It is only a start of what I plan on seeing though. Again, I get it, it’e rough to be me.

If I could have only one wish for everyone that has ever read anything I have written it would be that you could join me in the surreality of the last parts of this story. Travel is fatal to prejudice, it is good for the soul. Seeing the United States of America from the outside can provide a viewpoint that is simply incredible. Cal Fussman, a podcaster I listen to (and encourage everyone to hear), once talked of meeting a famous author who stayed drunk. I want to say it was Hunter S. Thompson but that isn’t right. Cal asked him how he could work drunk and not forget the good stuff. To which the author replied, “The good shit sticks.”

I can’t offer everyone a free ticket, but I can offer a free place to stay, a home base if you want it. Come on over to see the good shit. It’s all good shit, and it’ll stick.

For good measure I’ll hope you also get the problem of too much leave at least once, too. Though when I say that I run the risk of sounding like I’m bragging.